Sim Cases Cliff Notes - February 2018

/Every month we summarize our simulation cases. No deep dive here, just the top 5 takeaways from each case. This month includes severe traumatic brain injury and orbital compartment syndrome.

Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI)

1. The emergency provider should be able to rule-in or rule-out life threats identified on a CT brain and act on them.

The cranial computed tomograph (CT) has assumed a critical role in the practice of emergency medicine for the evaluation of traumatic intracranial emergencies.

A number of published studies have revealed a deficiency in the ability of emergency physicians to interpret head CTs. Nonetheless, in many situations the emergency physician must interpret and act upon head CTs initially without assistance from other specialists.

A 2009 study showed only 50% of CT studies read by teleradiology were completed in 60 minutes.

If you do not feel comfortable identifying life threatening head injuries on CT, check out our recent post on how to read an emergent head CT.

2. The brain is the spoiled organ living in the penthouse. It wants a specific physiology and gets very irritable when injured. Avoid a secondary brain injury by:

Achieving eucapnia (ETCO2 35-40 mm Hg)

End - tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) should be used on all ventilated patients to target eucapnia.

Maintaining adequate oxygention (SpO2 > 90%)

Hypoxia increases neuronal death and motor deficits, contributes to poor outcomes, and must be avoided at all costs.

Avoiding Hypotension (SBP < 90 mm Hg)

Cerebral autoregulation of cerebral blood flow is frequently either globally or regionally impaired in patients with TBI.

Older publications defined hypotension as a SBP < 90 mm Hg, but a recent large retrospective data set demonstrated a SBP < 110 mm Hg on admission to the ED was associated with an increased mortality in patients with moderate or severe TBI.

Significant morbidity and mortality occur when a patient experiences both hypoxia and hypotension, even when it is merely 1 brief instance of each.

3. Assume an elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) in severe TBI patients and take steps to reduce it.

The Cushing triad of bradycardia, hypertension and irregular respirations is present in only one-third of the time ICP is elevated (16).

Reducing ICP can improve cerebral perfusion pressure (CPP) and ultimately cerebral blood flow.

Bedside measures to reduce ICP:

Head of bed elevation < 30 degrees

Neck in neutral position, cervical collar not compressing jugular venous outflow from brain

Adequate post intubation analgesia/sedation to prevent spikes in ICP with coughing/intolerance (check out our post intubation sedation and analgesia guideline)

4. Identify and treat any coagulopathy.

Warfarin

Prothrombin complex concentrates

Fresh Frozen Plamsa 15-20 cc/kg

Vitamin K 10 mg IV

Heparin/low molecular weight heparin

Give protamine

0.5 - 1 mg/100 units heparin

0.5- mg/1 mg LMWH

Max 50 mg

Direct oral anticoagulants

Rivaroxaban/apixaban (reversible competitive antagonist of activated factor Xa)

Give Kcentra (25 units/kg) to help with clot formation at the site of bleeding.

As a last resort, consider recombinant activated Factor VII (20 mcg/kg)

NOTE: The strength of the evidence for these interventions is weak and limited.

Dabigatran (competitive antagonist of thrombin)

Give Idarucizumab 5 gm (2 x 2.5 gm doses) given 15 minutes apart to completely reverse dabigatran

Consider nephrology consult if patient in AKI and/or CrCL <50 mL/min

Aspirin/Clopidogrel

Platelets 6-8 random donor platelet concentrates

Evidence is mixed, no clear benefit

Desmopressin 0.3 mcg/kg IV

May shorten prolonged bleeding time but there is no clear evidence

5. If your patient has neurologic detioration, aggressively optimize CPP and institute additional ICP lowering therapies until your patient is able to get to a neurosurgeon.

Signs of herniation include:

Dilated and unreactive pupils (< 1 mm response)

Asymmetric pupils

Extensor posturing on motor examination

No motor response (not from spinal cord injury)

Drop in GCS score of more than 2 point with a best initial score of < 9

Management of the herniating patient:

Initiate hyperosmolar therapy

Mannitol 1 gram/kg

250 ml bolus of 3% hypertonic saline

Hyperventilation (temporary) to an ETCO2 of 30 mmg Hg

References

1. Schreiger DL et al: Cranial computed tomography interpretation in acute stroke. JAMA

1998;279:1293-1297.

2. Perron AD et al: A multicenter study to improve emergency medicine residents’ recognition of intracranial emergencies on computed tomography. Ann Emerg Med 1998;32:554-562.

3. Leavitt MA et al: Abbreviated educational session improves cranial computed tomography scan interpretations by emergency physicians. Ann Emerg Med 1997;30:616-621.

4. Alfaro DA et al: Accuracy of interpretation of cranial computed tomography in an emergency medicine residency program. Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:169-174.

5. Kreitzer N, Adeoye O. Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Anticoagulated Patients: Evidence-Based Emergency Department Management, Emergency Medicine Practice, December 2015, volume 17, No. 12.

6. Zammit, C, Knight, WA. Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Adults: Emergency Medicine Practice, March 2013, volume 15, No. 3.

7. Berry C, Ley EJ, Bukur M, Et al. Redefining hypotension in traumatic brain injury. Injury. 2011. [PubMed]

8. Chi JH, Knudson MM, Vassar MJ, et al. Prehospital hypoxia affects outcome in patients with traumatic brain injury: a prospective multicenter study. J Trauma. 2006; 61 (5) 1134-1141.[PubMed]

9. Stocchetti N, Furlan A, Volta F. Hypoxemia and arterial hypotension at the accident scene in head injury. J Trauma. 1996; 40(5): 764-767. [PubMed]

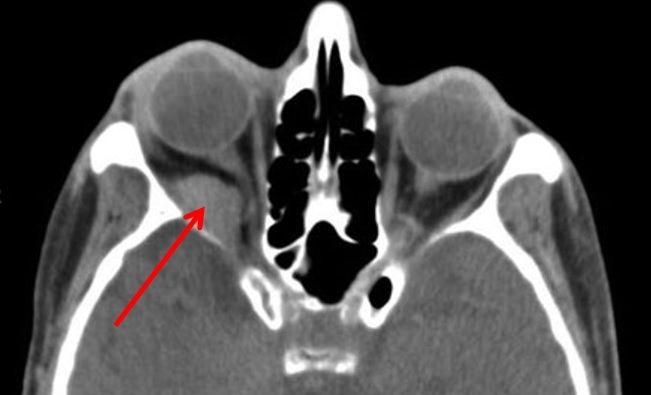

Orbital compartment syndrome

1. The presence of a retrobulbar hemorrhage and orbital compartment syndrome is an acute emergency requiring immediate care.

Tearing of blood vessels within the orbit and retro-orbital area causes an acute increase in the volume of the orbital contents.

This acute increase in pressure transmits to the globe, increasing intraocular pressure, decreasing ophthalmic perfusion and causing traction to the optic nerve.

2. Likely the most important factor in the outcome of orbital compartment syndrome is recognizing it as early as possible and treating promptly.

https://lifeinthefastlane.com/ophthalmology-befuddler-033/

The affected eye is typically proptotic with hemorrhagic swelling of the conjunctivae.

Ophthalmoscopic evaluation reveals a blanched ophthalmic artery in the presence of obvious retrobulbar pressure and ecchymosis around the eye.

The patient exhibits decreased visual acuity, and an afferent pupil defect is often seen.

3. Know your indications for a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis.

Primary Indications

Decreased visual acuity

Ocular pressure greater than 40 mm Hg

Proptosis

Secondary Indications

Afferent papillary defect (Marcus Gunn pupil)

Cherry-red macula

Ophthalmoplegia

Optic nerve pallor

A ruptured globe is a contraindication

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Iris_-_left_eye_of_a_girl.jpg

4. The goal of a lateral canthotomy is to release pressure on the globe, decrease IOP and allow retinal artery blood flow.

Inject 1% to 2% lidocaine with epinephrine.

Crush the lateral canthus with a small hemostat for 1 to 2 minutes to minimize bleeding.

Place the scissors across the lateral canthus and incise the canthus full thickness.

Find the superior and inferior crura of the lateral canthal tendon and release them from the orbital rim (this is typically identified via tactile feedback).

Some operators prefer to release the inferior crus and reassess IOP before considering release of the superior crus.

If done properly the lower lid should fall away from the lid margin.

Watch Dr. Fallon teach how to Perform a Lateral Canthotomy

References

1. Lateral Canthotomy on Dr. Larry Mellick's YouTube Page

2. Robers and Hedges' Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine. Chapter 62.

3. Vassallo, S., Hartstein, M., Howard, D., & Stetz, J. (2002). Traumatic retrobulbar hemorrhage: emergent decompression by lateral canthotomy and cantholysis. Journal of Emergency Medicine, 22(3), 251–256.[PubMed]

Written and Posted by Jeffrey A. Holmes, MD