Pediatric Diarrhea with Dr. Jay Larmon

/OVERVIEW

Diarrhea is a common complaint for our pediatric patients in the emergency department. Most pediatric diarrhea is not life threatening, and usually is treated with supportive care. However, there are important red flags to consider when assessing a pediatric patient with diarrhea. The usual etiology of diarrhea in pediatric patients is viral, however it can be due to bacterial, autoimmune, obstructive, allergic, and other disease processes.[1] Overall, assessing the hydration status of these patients is paramount.

ASSESSMENT

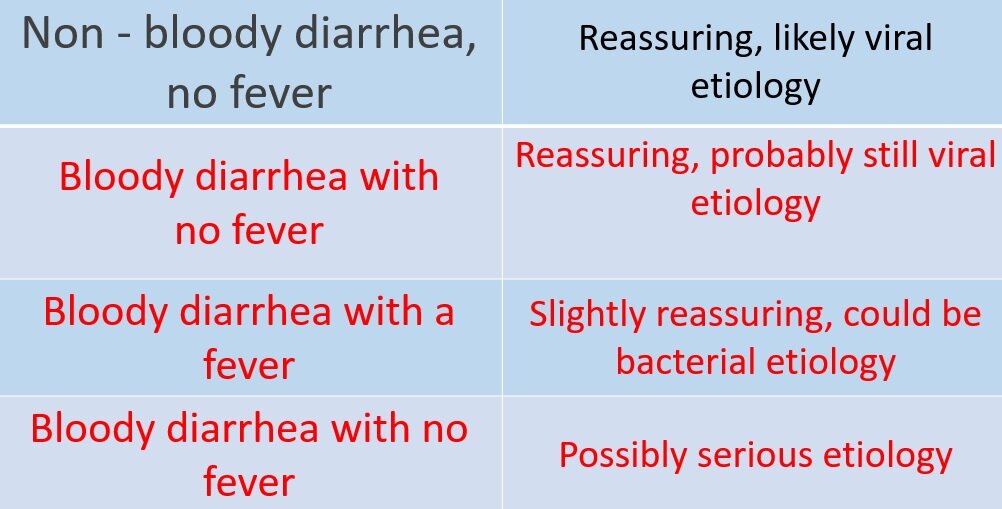

Initial assessment of the pediatric patient should always start with the patient’s vital signs and clinical presentation. Just like other patients in the emergency department, the child should be recognized as “sick” or “not sick.” If a patient has abnormal vitals, appears mottled with poor skin tugor, the patient is more likely to be “sick” and will warrant a more aggressive work up and rehydration strategy.[2] Important differentiators to assess if a patient has the potential to be “sick” or “not sick” include the presence of a fever or blood in the stool.[3] These presentations can be broken down into the four categories listed below.

As illustrated in the 4 categories, non-bloody diarrhea with or without a fever usually is a viral process, and only requires supportive care (i.e. hydration, etc). These patients typically are able to be rehydrated and discharged home with reassurance/return precautions to the parents.

Now bloody diarrhea with a fever is not as simple. This presentation has a higher probability to be bacterial as opposed to viral. How does this change our management? Well, patients have a greater potential to be sicker, and even though there is a higher chance of a bacterial infection these patients should NOT be started empirically on antibiotics.

E. Coli O157:h7

Why no antibiotics? Antibiotics can increase the risk of hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS) in the presence of shiga producing bacteria (E. Coli 0157:H7).[4] This risk of HUS developing from antibiotics can be as high as 25%. Most of these cases occur in children <10 years of age, with a triad of clinical features including:[5]

Acute renal failure

Thrombocytopenia

Microangiopathic Hemolytic Anemia (MAHA)

The majority of bloody diarrhea will resolve on its own regardless, so it is always important to hold on antibiotics initially, since there is limited benefit and the potential to harm with the possibility of HUS development. In this patient population, well appearing children can have stool cultures ordered and be referred to follow up as an outpatient.

REHYDRATION STRATEGIES

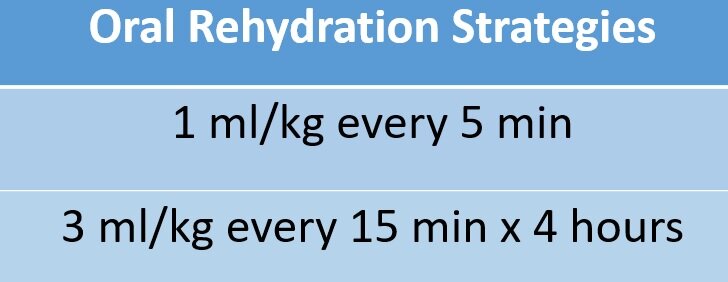

For the majority of pediatric patients with diarrhea, rehydration is the main treatment.[2] Oral rehydration is first line if tolerated, and the key is to get both glucose and salt in the solution if possible.[6] Consider explicit directions for oral rehydration if parents don’t have a plan, such as 1 ml/kg every 5 min or 3 ml/kg every 15 min for 4 hours. Some examples of rehydration solutions include Pedialyte, Gatorade or watered down apple juice.

If intravenous hydration is required or oral hydration is not tolerated, then a 10 to 20ml/kg fluid bolus should be considered. This can be followed by the maintenance fluid following the 4, 2, 1 rule for pediatric hydration:

4 ml/kg for first 10 kg

2 ml/kg for second 10 kg

1 ml/kg for remaining kg

Approximately 100 ml/kg/day is a good baseline for pediatric patients. However, consider 150% of this amount in patients with diarrhea. Illustrated below is a dehydration scale from Pediatric Dehydration to help guide management (Vega et al).[1,7]

From Vega RM, Avner JR: A prospective study of the usefulness of clinical and laboratory parameters for predicting percentage of dehydration in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 1997, 13(3):179-182.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The differential diagnosis for pediatric diarrhea is broad.[2,8,9] However, there are ways to narrow what the potential etiology based on history and exam. For instance, if the diarrhea has been on going for <10 days it is more likely to be infectious. If the diarrhea lasts more than 10 days, it is more likely to be autoimmune related or from another inflammatory processes.

As stated earlier, the assessment of pediatric diarrhea can be broken down into 4 categories. Of these, there are some overlap with etiologies, mostly between febrile bloody and non-bloody diarrhea, as some infectious processes can result in both. The table below illustrates a differential based on the 4 categories.[1]

Non-bloody diarrhea in an afebrile patient is almost always benign. It is usually a viral enteritis, but can also be from other causes such as antibiotic associated diarrhea or excessive fluid intake.

A febrile patient with non-bloody or bloody diarrhea could be of infectious etiology, which can present in many forms. Bloody diarrhea with fever could be viral, but as described earlier on in this section, has the greater potential to be bacteria. Some key pearls are illustrated below:

Salmonella

Typically from eggs and poultry, however can be derived from reptiles/amphibians

Bloody mucous stools

2 days incubation time

Fever, diarrhea commonly 5-7 days in duration

Asymptomatic carriers can continue to shed for a month (and still be infectious)

Campylobacter

Usually from summer months, outdoor undercooked meat

Is found in animal feces (avoid eating puppy/kitten stool!)

Incubation typically 2-5 days, with illness lasting up to 10 days

Association with Guillain-Barre syndrome

Shigella

Raw and unwashed vegetables

Most common to get passed around daycare

Seizures, AMS, coma

Rectal prolapse possible from excessive diarrhea

Fecal shedding

E. coli

One cause of HUS

Ground beef, unpasteurized food

Can last up to 7 days

Yersinia

Usually form pork or untreated water

Watery diarrhea that becomes bloody

Bigger deal for kids who are immunocompromised

Can present with RLQ pain (pseudoappy presentation)

Bloody diarrhea with no fever should always raise suspicion for something sinister or bad going on. These patients could have surgical emergency or other life-threatening disease processes (Need to think HUS).

HUS

Usually younger kids (4 years old is median age, ranges from 1 year to teens)

May not be apparent on labs until days 4-5, highest risk 7-14 days after infection

Three cardinal features

Acute Kidney Injury

Thrombocytopenia

MAHA

Fever may defervesce by time of presentation

1 week of bloody diarrhea and fever concerning for HUS

Order CBC, CMP, and UA to assess for hematuria, proteinuria, AKI, hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia

Those who present with fulminant HUS

60% require some form of dialysis

5% mortality

Surgical etiologies typically present with an acute abdomen (i.e. peritonitic signs, possible appears ill), usually with bloody diarrhea that appearing as the first bowel movement. Some important examples are illustrated below:

Obstruction

Malrotation

Ischemic bowel

Intussusception

NEC

Appendicitis (Does not always appears ill, especially early on in diseases process)

Another important aspect to consider when narrowing down a differential diagnosis is age. Different age groups tend to have different disease processes associated with them.[3] This is especially true when considering patients with bloody diarrhea.

Neonate Bloody diarrhea

Well appearing

Milk protein intolerance

Anal fissure

Swallowing maternal blood

Ill appearing

Malrotation

NEC

Coagulopathy

Younger child bloody diarrhea (~1 year old to ~8-year-old)

Intussusception

Infectious colitis

Gastritis

Meckel’s diverticulum

Vascular malformation

Older children/Adolescents (~5 year to ~15-year-old)

Juvenile polyps

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)

Appendicitis

WORK UP/DISPOSITION

Work up for the pediatric patient with diarrhea varies greatly depending on presentation. The majority of are able to go home, but as described in the assessment section, patients my present with severe dehydration and require admission with observation.

As illustrated in the assessment section, a careful examination of a patient’s dehydration status is key. Look for red flags of severe dehydration (i.e. crying without making tears, poor skin turgor, poor cap refill, irritable, etc). Patient’s with risk factors for fluid sensitivity, such as premature birth or cardiac disease, should have a lower threshold for admission.

In addition, if the patient appears sick or has peritonitic signs, the patient will require a “full court press.” In these patients, consider intra-abdominal emergencies (appendicitis, incarceration, etc). They will often require intravenous fluids and empiric antibiotics in addition labs (including blood cultures) and abdominal imaging.

If a surgical emergency is ruled out, either based on physical exam or labs/imaging, the disposition still comes down to hydration status. The bottom line is if the patient cannot maintain oral rehydration there should be a strong consideration to admit.

Overall, pediatric patients with diarrhea for the most part have a good prognosis and do well with oral hydration.

It is important to always consider the etiology of the diarrhea, as well as hydration assessment.

Always consider life threatening processes in patients with previous risk factors or a concerning exam

Remember the 4 categories that pediatric diarrhea:

Non-bloody diarrhea without fever

Most likely viral

Generally, not sick

Treat symptomatically, rehydration instructions to parents

Non-bloody diarrhea with fever

Most likely still viral

Treat symptomatically, most patients still do well

Bloody diarrhea and fever

Likely bacterial enteritis/colitis

NO empiric antibiotics (can precipitate HUS if antibiotics are given)

Culture stools, generally healthy/well, can handle 2-3 days diarrhea while cultures result

Bloody diarrhea without a fever

HUS

IBD in older kids

Surgical emergency (malrotation, intussusception, etc)

References

Burns CE, Richardson B, Brady MA: Pediatric primary care case studies. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2010. [Chapter Link]

Brady K: Acute gastroenteritis: evidence-based management of pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract 2018, 15(2):1-25. [Pubmed]

Ludwig S, Shah SS: Symptom-based diagnosis in pediatrics, Second edition. edn. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014. [Chapter Link]

Tarr PI, Gordon CA, Chandler WL: Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli and haemolytic uraemic syndrome. Lancet 2005, 365(9464):1073-1086. [Pubmed]

Cleary TG: Escherichia coli that cause hemolytic uremic syndrome. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1992, 6(1):163-176. [Pubmed]

Practice parameter: the management of acute gastroenteritis in young children. American Academy of Pediatrics, Provisional Committee on Quality Improvement, Subcommittee on Acute Gastroenteritis. Pediatrics 1996, 97(3):424-435. [Pubmed]

Vega RM, Avner JR: A prospective study of the usefulness of clinical and laboratory parameters for predicting percentage of dehydration in children. Pediatr Emerg Care 1997, 13(3):179-182. [Pubmed]

Larcher VF, Shepherd R, Francis DE, Harries JT: Protracted diarrhoea in infancy. Analysis of 82 cases with particular reference to diagnosis and management. Arch Dis Child 1977, 52(8):597-605. [Pubmed]

Denno DM, Shaikh N, Stapp JR, Qin X, Hutter CM, Hoffman V, Mooney JC, Wood KM, Stevens HJ, Jones R et al: Diarrhea etiology in a pediatric emergency department: a case control study. Clin Infect Dis 2012, 55(7):897-904. [Pubmed]