Simulation Cases Cliff's Notes - 2/15/17

/Every month we summarize our simulation cases. No deep dive here, just the top 5 takeaways from each case.

Peri-Mortem C-Section

1. If you suspect a sick obstetric patient coming, call for help early and get your equipment ready

Call your dream team if they are available (OB, NICU, Trauma)

Get C – section equipment ready (If you don't have a "c-section kit" at your institution, a chest tube or thoracotomy tray can substitute)

2. Don't delay when the procedure is indicated

This is a resuscitative intervention for mother - it is the best for both the unborn child and her

Viable fetus in mother (24 weeks) + cardiac arrest = perimortem c-section

Fundus at or above umbilicus ≥ 20 weeks is the best way to clinically estimate near 24 weeks

No physician in the US has been prosecuted for performing a peri-mortem c-section [2]

3. All you have to remember: 24 – 5 – scalpel and scissors

24 weeks is approximate age of viability

5 minutes from cardiac arrest to get baby out to maximize neonatal survival chances [1]

Essential equipment are scalpel (#10) and scissors

4. Continue CPR/resuscitation on Mom during and after the c-section

- There are numerous case reports of return of spontaneous circulation after the c-section

5. Rapid extraction while minimizing maternal/fetal injury is the goal

Be sterile whenever possible, but don’t delay c-section for prep

Make a vertical incision with #10 blade, umbilicus to pubic symphysis through the peritoneum

Deflect bladder, make a 5 cm vertical incision through lower uterine segment

Use bandage scissors to incise uterus, remove baby, clamp and cut cord

Remove placenta and membranes

References

1. Katz V.L., Dotters D.J., Droegemueller W. Perimortem cesarean delivery. Obstet. Gynecol. 1986;68:571–576.

2. Stallard TC, Burns B. Emergency Delivery and Peri-mortem c-section. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003 Aug;21(3):679-93.

HERE IS A GREAT REVIEW OF WHEN AND HOW TO DO A PERI-MORTEM C-SECTION

Hemophilia and Head Trauma

1. The most common inherited bleeding disorders are:

Factor VIII deficiency (hemophilia A)

Factor IX deficiency (hemophilia B)

2. The severity of factor VIII and factor IX deficiencies is determined by the factor activity level: mild (5%-40%), moderate (1%-5%), and severe (< 1%). Severe hemophilia comprises the largest group [1]

3. Intracranial hemorrhage has exceeded HIV as a leading cause of mortality [1]

4. Intracranial hemorrhage can occur with or without a history of trauma and is much more likely to occur in patients with severe hemophilia

In a French study, only 62% of patients younger than 15 years reported a history of trauma [2]

Diagnosis was delayed in 43% of these patients, and treatment was delayed in 37%

Significant headaches (even without trauma) must be taken very seriously in the hemophiliac

5. Emergency management of hemorrhage for patients with a congenital bleeding disorder centers on increasing the circulating levels of deficient clotting factors

- If factor replacement is unavailable, cryoprecipitate (for factor VIII deficiency) or fresh frozen plasma (FFP) (for factor IX deficiency) may be used as a last resort

The goal of factor replacement is generally considered to be 40%-50% for minor bleeds and 80%-100% for major hemorrhages [3]; for major hemorrhages, assume the patient has close to 0% activity

One unit/kilogram of factor VIII concentrate will increase factor VIII activity by 2%; therefore, to achieve 100% correction, 50 U/kg must be administered

One unit/kilogram of factor IX concentrate will only increase factor IX activity by 1%; therefore, twice as much factor IX must be administered for the same effect: 100 U/kg are necessary to achieve 100% correction[3]

References

1. Darby SC, Wan SW, Spooner RJ, et al. Mortality rates, life expectancy and causes of death in people with hemophilia

A or B in the United Kingdom who were not infected with HIV. Blood 2007 Aug;110(3): 815-826.

2. Stieltjes N, Calvez SN, Demiuel V, et al. Intracranial haemorrhages in French haemophilia patients (1991-2001): clinical

presentation, management and prognosis factors for death. Haemophilia 2005 Sep;11(5):452-458

3. Hemophilia of Georgia, World Federation of Hemophilia. Protocols for the treatment of hemophilia and von Willebrand

disease. April 2008, No. 14.

Accidental Hypothermia

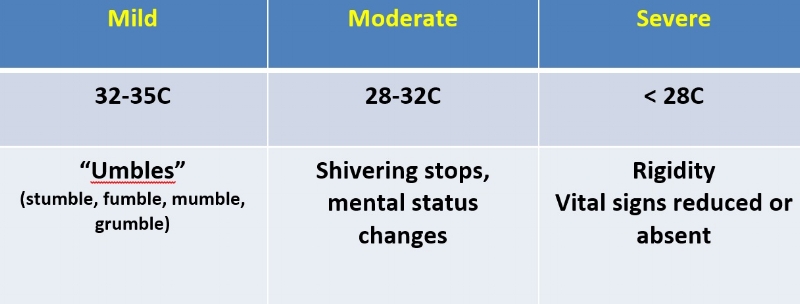

1. Stratify the severity of hypothermia (temperature and functional characteristics; use clinical exam and rectal temperature to gauge severity)

2. No one is dead until they are warm and dead…..unless they are already dead

Look for signs of dependent lividity

Frozen solid, chest noncompliance

Ice in airway

Hyperkalemia on blood draw (> 14) [1,2]

3. Don't forget to look for other causes of altered mental status

Head trauma

Hypoglycemia

Intoxication

Overdose

4. Match your treatment with your hypothermia severity [1]

5. Modify your ACLS [1]

If severely hypothermic and there is an organized rhythm on monitor, consider it a perfusing rhythm and avoid CPR (confirm perfusing rhythm by bedside echo, doppler pulses)

Shock once for vfib/vtach, ACLS drugs x 1 until core temperature > 30C

References

1. Services DoHaS, Health DoP, EMS SoCHa. State of Alaska Cold Injuries Guidelines. Juneau, Alaska (Guideline) 2014.

2. Silfvast T, Pettilä V. Outcome from severe accidental hypothermia in Southern Finland--a 10-year review. Resuscitation. 2003 Dec;59(3):285-90.

Severe Facial Trauma/Fractures

1. Be ready to establish a definitive airway early

Concomitant head trauma can cause altered mental status

Active hemorrhage can compromise the airway

Significant mandible and midface fractures can lead to airway edema and obstruction

2. If significant hemorrhage results from facial fractures, establish initial control with intranasal, nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal packing

3. The risk of traumatic brain injury, ranging from a simple concussion to severe intracranial and extra-axial hemorrhages, increases in the setting of facial trauma[1]

- Consider adding a CT head in addition to your facial bones CT

4. The incidence of blunt cerebrovascular injuries (BCVI), identified by the Denver screening criteria, found a significant association for BCVI with mandible fractures, Le Fort II and III fractures, as well as scalp degloving injuries [2]

5. Don't forget the frontal sinus

- Frontal sinus fractures that involve the posterior wall require neurosurgical consultation as they can lead to dural violation, CSF leak, disruptions of the anterior cranial fossa or CNS infections.

References

1. Gassner R, et al. Craniomaxillofacial trauma in children: A review of 3,385 cases with 6,060 injuries in 10 years. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;62(4): 399-407.

2. Burlew CC, et al. Blunt cerebrovascular injuries: Redefining screening criteria in the era of noninvasive diagnosis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2012;72(2):330-335; discussion 336-337, quiz 539.

Written by Jeffrey A. Holmes, MD